Continued Article by Jim Krane (Rice University), Yahoo! News, 11/17/22

Motivating U.S. producers to act has been the big hurdle. ~ The Biden administration is aiming for an 87% reduction in methane emissions below 2005 levels by the end of the decade. To get there, it has reimposed and strengthened U.S. methane rules that were dropped by the Trump administration. These include requiring drillers to find and repair leaks at more than 1 million U.S. well sites.

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 further incentivizes methane mitigation, including by levying an emissions tax on large oil and gas producers starting at $900 per ton in 2024, increasing to $1,500 in 2026. That fee, which can be waived by the Environmental Protection Agency and doesn’t affect small producers or leaks below 0.2% of gas produced, is based on the social cost to society from methane’s contribution to climate damage.

Customers are also putting pressure on the industry. Regulatory indifference by the Trump administration to U.S. methane flaring and venting led to cancellation of some European plans to import U.S. liquefied natural gas. Reducing methane isn’t always straightforward, though, particularly in the U.S., where thousands of oil companies operate with minimal oversight.

A company’s methane emissions aren’t necessarily proportional to its oil and gas production, either. For example, a 2021 study using data from the EPA found Texas-based Hilcorp Energy reporting nearly 50% more methane emissions than ExxonMobil, despite producing less oil and gas. Hilcorp, which specializes in acquiring “late life” assets, says it is working to reduce emissions. Other little-known producers have also reported large emissions.

Investor pressure has pushed several publicly traded companies to reduce their methane emissions, but in practice this sometimes leads them to sell off “dirty” assets to smaller operators with less oversight. In such a situation, the easiest way to encourage companies to clean up is via a tax. Done right, companies would act before they had to pay.

Using technology to keep emissions in check ~ Unlike carbon dioxide, which lingers in the atmosphere for a century or more, methane only sticks around for about a dozen years. So, if humans stop replenishing methane stocks in the atmosphere, those levels will decline.

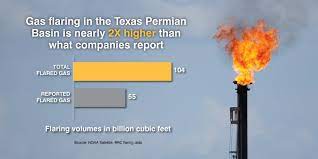

A review of methane leaks in the Permian Basin shows the big impact that some regions can have. ~ Researchers found that gas and oil operations in the Permian, in west Texas and New Mexico, had a leakage rate estimated at 3.7% in 2018 and 2019, before the pandemic. A 2012 study found that leakage rates above 3.2% make climate damage from using natural gas worse than that from burning coal, which is normally considered the biggest climate threat.

Methane leaks used to escape detection because the gas is invisible. Now, the proliferation of satellite-based sensors and infrared cameras makes detection easy.

Companies such as GTI Energy’s Veritas, Project Canary and MiQ have also launched to assist natural gas producers in reducing emissions and then verifying the reductions. At that point, if leaks are less than 0.2%, producers can avoid the federal fee and also market their output as “responsibly sourced” gas.

>>> This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Jim Krane, Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.