>>> Adapted from the Article by Elizabeth Kolbert, New Yorker Magazine, November 28, 2022

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tracks weather-related disasters in the U.S. that cause more than a billion dollars’ worth of damage. According to NOAA, in the nineteen-eighties the U.S. saw an average of three such disasters per year. In the nineteen-nineties, the average was five per year; in the two-thousands, it was six; and in the twenty-tens it jumped to twelve. (The figures have been adjusted for inflation.)

In 2020, a record-shattering twenty-two disasters costing more than a billion dollars struck the country. This year is nearly on pace to match that record, with fifteen such disasters by October, including Hurricane Ian, which is likely to prove one of the most expensive storms in American history.

Adam B. Smith, a NOAA researcher, has written that a disastrous number of disasters “is becoming the new normal.” The rise is partly a function of more people living in vulnerable areas, such as floodplains. But increasingly it’s a function of climate change.

In the future, the costs may climb steeply or they may climb precipitously. All our infrastructure has been built with the climate of the past in mind. Much of it will have to be rebuilt and then, as the world continues to warm, rebuilt again.

To protect the Houston area (and its many petrochemical plants) from rising seas and storm surges, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is planning to erect a huge system of gates at the mouth of Galveston Bay. The price tag for the project, known as the Ike Dike, is estimated at thirty billion dollars.

Norfolk, Virginia, is hoping to stave off the water with a $1.5-billion series of barriers, levees, and tidal gates, and Charleston, South Carolina, is looking to build a billion-dollar flood wall. Some places — large swaths of Miami, for instance — may prove impossible to defend, meaning that real estate now valued in the hundreds of billions of dollars will have to be written off.

#######+++++++#######+++++++########

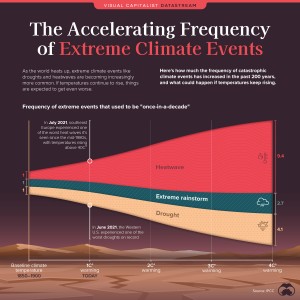

~. ~. The Accelerating Frequency of Extreme Weather ~. ~.

From an Article by Carmen Ang, Visual Capitalist, January 13, 2022

The world is already witnessing the effects of climate change.

A few months ago, the western U.S. experienced one of the worst droughts it’s seen in the last 20 years. At the same time, southern Europe roasted in an extreme heatwave, with temperatures reaching 45°C (113°F)in some parts.

But things are only expected to get worse in the near future. Here’s a look at how much extreme climate events have changed over the last 200 years, and what’s to come if global temperatures keep rising.

A Century of Warming & More of Same Going Forward

The global surface temperature has increased by about 1°C (1.8°F) since the 1850s. And according to the IPCC, this warming has been indisputably caused by human influence.

As the global temperatures have risen, the frequency of extreme weather events have increased along with it. Heatwaves, droughts and extreme rainstorms used to happen once in a decade on average, but now:

Heatwaves are 2.8x more frequent

Droughts are 1.7x more frequent

Extreme rainstorms are 1.3x more frequent

By 2030, the global surface temperature is expected to rise 1.5°C (2.7°F) the Earth’s baseline temperature, which means that:

Heatwaves would be 4.1x more frequent

Droughts would be 2x more frequent

Extreme rainstorms would be 1.5x more frequent

The Ripple Effects of Extreme Weather

Extreme weather events have far-reaching impacts on communities, especially when they cause critical system failures.

Mass infrastructure breakdowns during Hurricane Ida this year caused widespread power outages in the state of Louisiana that lasted for several days. In 2020, wildfires in Syria devastated hundreds of villages and injured dozens of civilians with skin burns and breathing complications.

As extreme weather events continue to increase in frequency, and communities become increasingly more at risk, sound infrastructure is becoming more important than ever. [The importance of net-zero projects cannot be over emphasized. WiN = When is Now!].

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Atmospheric rivers endanger the West

By Dave Marston, Writers on the Range, January 23, 2023

Moab, Utah, gets just eight inches of rain per year, yet rainwater flooded John Weisheit’s basement last summer. Extremes are common in a desert: Rain and snow are rare, and a deluge can cause flooding.

Weisheit, 68, co-director of Living Rivers and a former Colorado River guide, has long warned the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation that its two biggest dams on the Colorado River could become useless because of prolonged drought.

Although recently, at a BuRec conference, he also warned that “atmospheric rivers” could overtop both dams, demolishing them and causing widespread flooding.

Weisheit points to BuRec research by Robert Swain in 2004, showing an 1884 spring runoff that delivered two years’ worth of Colorado River flows in just four months.

California well knows the damage that long, narrow corridors of water vapor — atmospheric rivers — can do. Starting in December, one atmospheric storm followed another over the state, dumping water and snow on already saturated ground.

The multiple storms moved fast, sometimes over 60 miles per hour, and they quickly dropped their load. Atmospheric rivers can carry water vapor equal to 27 Mississippi Rivers.

These storms happen every year, but what makes them feel new is their ferocity, which some scientists blame on climate change warming the oceans and heating the air to make more powerful storms.

In California, overwhelmed storm drains sent polluted water to the sea. Roads became waterways, sinkholes opened up to capture cars and their drivers, and houses flooded. At least 22 people died.

PHOTO ~ Glen Canyon Dam under construction c. 1960-63.

(Photo courtesy of USBR)

Where do these fast-moving storms come from? Mostly north and south of Hawaii, then they barrel directly towards California and into the central West, says F. Martin Ralph, who directs the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego.

“Forty percent of the snowpack in the upper Colorado in the winter is from atmospheric river storms penetrating that far inland,” he adds.

The real risk is when storms stack up as they did in California. That happened in spades during the winter of 1861-1862, in the middle of a decade-long drought, when the West endured 44 days of rain and wet snow. California Governor-elect Leland Stanford rowed to a soggy oath-of-office ceremony in flooded Sacramento, just before fleeing with state leaders to San Francisco.

Water covered California’s inland valley for three months, and paddle wheel steamers navigated over submerged farmlands and inland towns. The state went bankrupt, and its economy collapsed as mining and farming operations were bogged down, one quarter of livestock drowned or starved, and 4000 people died.

In Utah that winter, John Doyle Lee chronicled the washing away of the town of Santa Clara along the tiny Santa Clara River near St. George. Buildings and farms floated away leaving only a single wall of a rock fort that townspeople had built on high ground.

Weisheit knows this history well because he’s been part of a team of “paleoflood” investigators, a group of scientists and river experts. To document just how high floodwaters rose in the past, researchers climb valley walls. The Journal of Hydrology says they seek “fine grained sediments, mainly sand.”

It’s a peculiar science, searching for sand bars and driftwood perched 60 feet above the river.

The Green River contributes roughly half the water that’s in the Lower Colorado River, and in 2005, Weisheit and other investigators found six flood sites along the Green River near Moab, Utah. Weisheit says several sites showed the river running at 275,000 cubic feet per second (cfs).

If the Green River merged with the Colorado River, also at flood, the Colorado River would carry almost five times more water than the 120,000 cfs that barreled into Glen Canyon Dam, some 160 miles below Moab, in 1984. That epic runoff nearly wiped out Glen Canyon Dam.

Now that we’ve remembered the damage that atmospheric river storms can do, Weisheit believes that Bureau of Reclamation must tear down Glen Canyon — now.

He likes to quote Western historian Patty Limerick, who told the Bureau of Reclamation, at a University of Utah conference in 2007, what she really thought: “The Bureau can only handle little droughts and little floods. When the big ones arrive, the system will fail.”

>>> Dave Marston is the publisher of Writers on the Range, writersontherange.org, an independent nonprofit dedicated to spurring lively conversation about the West.

Source: https://writersontherange.org/atmospheric-rivers-endanger-the-west/