From the Newsletter by Patricia Popple, Frac Sand Sentinel, January 15, 2023

If the Planet is Warming, Why am I Freezing? ~ Scientists for a long time have been looking at the causation of changing weather patterns and climate and how these two elements are instrumental in making changes for us all. Take a look at this 5 minute link to help resolve this question in your mind.

Once you have viewed the response to the question above, the concerns regarding the Sixth Mass Extinction become even clearer by watching this clip from the 60 Minutes broadcast:

Paul Ehrlich was on the 60 Minutes show (I could not believe he is 90) but immediately friends recalled seeing him several times on the Johnny Carson Show, beginning in the early 70s.

Paul Ehrlich on Johnny Carson ~ YouTube

“Who is going to change their living habits?” There are some folks out there who deny and obstruct science of any kind.

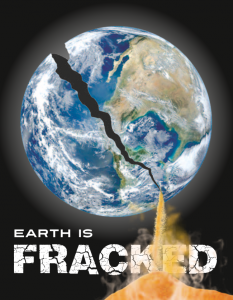

Those of us who have been involved in fighting the frac sand issues realize the value of our experiences with the hazards of this activity as well as the political differences that divide and conquer us whenever issues of this nature arise. Yet we do have a planet to protect and preserve and make healthier, not only for ourselves but for those who come after us.

NOTE ~ Patricia Popple is the Editor of the Frac Sand Sentinel in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin. The web site is wisair.wordpress.com and for additional information, click here for panoramic aerial views of frac sand mines, processing plants, and trans-load facilities. FracTracker.org is also an excellent source of information and a picture source. FRAC SAND SENTINEL | 561 SUMMIT AVENUE, Chippewa Falls, WI 54729

See Also: Climate Change and the New Age of Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert, New Yorker Magazine, May 13, 2019

People easily forget “last of” stories about individual species, but the loss of nature also threatens our existence.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

S = “Shortfall” ~ By Elizabeth Kolbert, A, B, C’s of Climate Change, New Yorker Magazine, November 28, 2022

And what goes for the U.S. goes for the rest of the world. China is currently the world’s biggest emitter of GHG on an annual basis. It has said that it will reach net zero by 2060. In the early months of 2022, Beijing approved !ve enormous new coal-!red generating plants. In August, when a punishing drought cut into hydropower production along the Yangtze River, the country hit a new record for daily coal consumption.

Climate Action Tracker, an independent research group based in Berlin, rates China’s climate policies as “highly insufficient” and notes that the country has recently “reneged” on promises to shift away from coal.

India, which is now the world’s third-biggest emitter — one rung behind the U.S. — has declared that it will reach net zero by 2070. Meanwhile, its emissions are rising fast. This past spring, when India was hit with a devastating heat wave and power use surged, its Coal Ministry announced plans to reopen a hundred mines that had been closed as unpro!table.

Russia is the world’s fourth-largest emitter. It is aiming, on paper at least, to reach net zero by 2060. But it has taken almost no action to rein in its emissions, and this seems unlikely to change anytime soon. In 2003, President Vladimir Putin joked that warming would enable Russians to “spend less on fur coats”; more recently, he has blamed climate change on “some invisible shifts in the galaxy.”

The European Union’s pledge to hit net-zero emissions by 2050 is written into E.U. law. But, after Russia cut gas deliveries to the bloc, several countries, including Germany and the Netherlands, announced plans to fire up old coal plants or extend the lives of plants that had been slated to close. “The war in Ukraine is putting climate action on the back burner,” the U.N. Secretary-General, António Guterres, lamented last month.

A recent study by a consortium of research institutes in Europe and the U.S. concluded that only five per cent of the hundred and twenty-eight countries that have set the goal of reaching net zero have taken the requisite first steps. It found an “alarming lack of credibility” to most of the commitments.

The broken promises extend in all directions. At last year’s COP, held in Glasgow, a hundred and forty countries vowed to put a stop to “forest loss,” another major source of greenhouse-gas emissions. (A single full-grown tree can store as much as seven tons of carbon.) Among the signatories of the declaration was Brazil; in the six months following the conference, deforestation rates in the country soared to new highs.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo also signed the forest pledge. In July, the D.R.C. announced that it was opening thirty huge tracts, encompassing an estimated twenty-!ve million acres of rain forest and two million acres of peatlands, to oil and gas exploration. (Some of the tracts overlap Virunga National Park, a refuge for critically endangered mountain gorillas.)

Then there are the pledges of financial support. The hundred billion dollars a year promised in Copenhagen to developing nations have yet to materialize. By some estimates, the shortfall runs to twenty billion dollars a year; by others, it’s four times that amount.

“To be charitable, this is a manifestation of the inability of the developed countries to deliver,” Saleemul Huq, the director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, told me. “To be uncharitable, they just don’t give a damn. Unfortunately, the uncharitable interpretation seems to be more valid.”