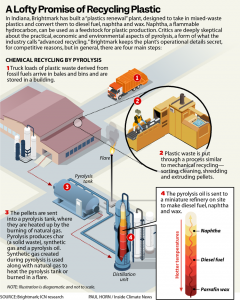

Generally, pyrolysis processes generates far worse chemical pollution than incineration (click to expand)

.

.

From an Article by James Bruggers, Inside Climate News, 9/11/22

.

.

EPA Rules Under Review

Brightmark and its expansion plans come as the Environmental Protection Agency weighs how to regulate pyrolysis, with air quality and economics on the line.

EPA regulations now consider pyrolysis to be incineration, which brings tighter clean-air controls. But in the waning months of the Trump administration, EPA proposed an industry-friendly rule change that stated that pyrolysis is not combustion and thus should not be regulated as incineration.

“The appropriate regulation of this is really critical if you want to scale advance recycling, and you want to use more recycled material in your products,” said Joshua Baca, vice president of plastics for the American Chemistry Council, a leading lobby for the plastics industry.

Facilities that turn plastic waste into gas and then burn the gas to help generate heat for the pyrolysis process are in effect still burning the plastic, with at least some oxygen involved in both steps in the process, said attorney James Pew, director of the environmental group Earthjustice’s clean air practice.

“The absolute crux of this issue is whether these new incinerators have to put on controls, like with conventional incinerators, or whether they can skip that and not control or monitor their pollution,” said Pew.

Pressure is mounting on EPA, which, according to a spokeswoman, is gathering public input and still deciding its next steps for pyrolysis and a related technology known as gasification. In mid July, 35 lawmakers including Rep. Jamie Raskin, and Sens. Bernie Sanders and Corey Booker, wrote to the EPA, urging the agency to fully regulate plastic chemical recycling’s emissions and to stop working to promote the technology as a solution to the plastics crisis.

“Chemical recycling contributes to our growing climate crisis and leads to toxic air emissions that disproportionately impact vulnerable communities,” the lawmakers wrote.

Struggling to Meet Its Timetable

At the end of July, Brightmark Chief Executive Officer Bob Powell, in a Zoom interview from his San Francisco office, said the company was still working to work the last kinks out of its system. “We have operated it at startup levels,” Powell said. “We’re just now at the point where we’re mechanically complete, and we’re starting to … create those finished products.”

Groundbreaking was in 2019, after the company secured a $260 million financing package that included $185 million bonds through the Indiana Finance Authority, underwritten by Goldman Sachs. Authority officials said the financing is not a state debt and Brightmark will be entirely on the hook to repay them.

The company has struggled to meet its timetable, Schabel acknowledged on the tour of the plant. He said it has taken time to secure an optimal stream of plastic waste for which there was no market, deal with delays caused by the Covid pandemic and navigate the challenges of developing new technology.

Dell said she’s not surprised, adding that she believes that despite the overall abundance of plastic waste on the planet, securing a steady stream of the kind of plastic waste the company has targeted will be an insurmountable challenge. The company has said it will largely recycle mixed, post-consumer plastics, the kind that millions of Americans toss in their recycling bins every week.

But these wastes are made of many different kinds of plastics, with a range of chemical compositions, and they vary by city and season, she said. Some of the plastics harm the pyrolysis process by introducing oxygenated molecules which reduce yield and lower the quality of the pyrolysis oil output, she said.

Polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, common in consumer product labels, films and packaging, adds chlorine atoms that can cause equipment corrosion and contaminate the pyrolysis oil, she said. Household plastic waste from municipal waste-handling facilities is also contaminated with other garbage that upsets the pyrolysis process, including liquids, food, dirt, paper, glass, metal and polystyrene foam, Dell added.

“There’s this perception that there’s so much plastic waste in the world and in the country, which there is,” Dell said. “And then they hold up this magic plant that they say is going to recycle everything from households all mixed together, and people believe it. But it can’t. It can’t handle the changing variety of household plastic waste and the unavoidable contamination.”

Beckman, the University of Pittsburgh professor, said he was particularly surprised to see the company plans to accept PVC. “I do not know how they’re taking in PVC, and not getting something you really don’t want,” he said. That could include dioxins or other possible unwanted chlorinated products and more char, he added.

The EPA considers dioxins to be persistent organic pollutants, highly toxic and potentially cancer-causing “There have been people who have looked at this in different ways over the years, asking, ‘What can we do?’ And honestly, what you can do is make sure (PVC) never goes into a pyrolysis unit,” Beckman said.

For his part, Schabel acknowledged taking in mixed plastic wastes can be a challenge but said they can all be handled by the company’s technology, which he described as proprietary. He declined to go into specifics about the proprietary nature of the company’s technology, which was developed by RES Polyflow, the Ohio company he served as chief executive officer before joining Brightmark.

He said the plant can process PVC, but added: “If we pull out more of it, we get a better yield.”

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I will be discussing health effects of plastics next Saturday at 3 PM via zoom.

Register here now for the Zoom on this coming Saturday, September 24th:

https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZIpceqppzgvHNGvw3TLKM0WXmr0Ra9OkMWE