CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis “Milestones” on Milestone, Sony Music Entertainment Inc.]

CURWOOD: Each Earth Day marks an important milestone for Living on Earth. In April of 1991 Living on Earth started broadcasting weekly on public radio, and we’ve been hitting the airwaves ever since. Biologist and Woods Hole Research Center founder George Woodwell helped inspire me to start this show when he told me that global warming from burning fossil fuels and forests would likely melt the Arctic. He explained that as the permafrost released its CO2 and methane, those added greenhouse gases would cause more warming and melt the arctic even more, which would add yet more carbon to the atmosphere. At some point these self-reinforcing reactions, this feedback loop, would be beyond human control.

CURWOOD: As a journalist it seemed to me that if what George described was allowed to get out of hand, little else would matter much for society. So I decided that climate change and so many other environmental stories needed reporting, and here we are. Now, many things have changed since 1991 and science has made some amazing advances. The human genome was sequenced, and gene therapy began. The Hubble telescope gave us fantastic views of deep space. Technology gave us the world wide web, which made e-commerce, Google and Facebook possible, and the invention of the smart phone put the world in our pocket. And in politics and society, South Africa ended apartheid and freed Mandela and the US elected its first president of direct African descent, Barack Obama.

But the numbers show we are still failing to preserve the climate. Over the last 30 years human-caused emissions have increased by 60 percent. Today the atmosphere holds the equivalent of about 500 parts per million of CO2. That is not good news. We began the industrial age in 1760 with concentrations of CO2 at about half those levels and we are now living through the hottest decade in modern human history.

As a result we are seeing record breaking heat waves and wildfires from California to Siberia, floods, rising sea levels and shrinking Arctic sea ice. Not to mention, record-breaking Atlantic hurricane seasons, searing droughts and massive tornado clusters. And all this climate disruption is a result of just a single degree centigrade rise in average earth surface temperatures since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

But our broadcast today is not simply a look back or lament. We are also looking ahead, to shine a light on some possibilities to head off climate disruption before civilization as we know it becomes untenable. We will consider the possibilities of economics, politics, applied science and technology to address climate disruption, though so far they have fallen short.

So, we will look to see what they may be missing. And since we humans have caused the climate emergency, we’ll also consider how we can think differently about our place on this planet. For some clues we’ll look to some ancient wisdoms and contemporary anthropology.

[MUSIC: Brian Rolland’s “Along the Amazon” on Dreams of Brazil, On The Full Moon Productions]

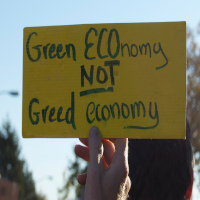

CURWOOD: Correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation, but there are two striking trends that run parallel to the alarming rise in global warming gases. One is the astonishing growth of economic wealth, and in recent years that increase in wealth in the US has been confined to the very richest. In fact, most families in the US have seen little or no gain, with many losing economic power, as many young adults today can’t afford to buy homes like the ones they grew up in.

The other trend is the loss of confidence in government action at the national and local levels and the failure of international rules governing climate change emissions to go beyond the honor system. The concentration of economic and political power related to those trends has historically thrived on the extraction and burning of fossil resources. Climate policy critics including Van Jones, Kristina Karlsson and Bill McKibben say that has to change, if we are to halt our present march toward climate Armageddon.

Kristina Karlsson is a program manager for the climate and economic transformation team at the Roosevelt Institute.

JONES: The first industrial revolution hurt the people and the planet, too. And, the next industrial revolution has to help the people and the planet.

KARLSSON: Meaningfully addressing climate requires an economic transformation in basically all corners of our economy.

MCKIBBEN: I think we’re reaching a turning point. I think that the political power of the fossil fuel industry has begun to wane after a century or two of waxing. And our job is to accelerate that to push hard for really rapid, rapid change.

CURWOOD: But right now despite pledges and promises from businesses and governments the nascent momentum for rapid change has been put on ice with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The resulting spike in oil and natural gas prices now has the Biden Administration saying drill baby, drill.

ORESKES: The war should be a reminder to us of how many good reasons there are to act on climate besides just the climate system itself. Europe is essentially hostage to Russian gas. And this is one of those things that breaks my heart.

CURWOOD: Naomi Oreskes is a Professor of the History of Science and Affiliated Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University.

ORESKES: Because if we had started the process of transitioning away from fossil fuels to renewable energy. If we started that process back in 88, when the IPCC was first gathered, or in 1990, when they first issued their report, or 1992, when the world’s nations signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, we could have made that transition by now 30 years is a long time in the history of technology. It’s enough time to build solar farms and wind farms, and improve your electricity grid. We could have fixed this problem.

Instead now we’re essentially hostage to the fossil fuel industry. So at this very moment of crisis, when we absolutely need to stop using fossil fuels. We’re in a situation where the Europeans are saying, well, well, we can’t live without fossil fuels. So this is really a kind of, it’s kind of a tragedy of historic proportions. I do think historians will be writing about this for years to come.