Remembering Naturalists E.O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy with Jane Lubchenco (Transcript)

Remembering Naturalists E.O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy with Jane Lubchenco (Transcript)

>> From the Broadcast by Steve Curwood, Living on Earth, January 7, 2021

CURWOOD: The world lost several notable people in the waning days of 2021, including two leading naturalists, who died just a day apart at the end of December. ~~ Edward, or “E.O.” Wilson and Tom Lovejoy were pioneers in the field of conservation biology. And as they documented the steep declines in life on this planet they also gave clarion calls to protect it. Harvard Professor E.O. Wilson specialized in the tiniest of creatures and was nicknamed “Ant Man”. But his work on biodiversity took a planet-sized view of the extinction crisis.

WILSON: I like to call it, “One Earth, one experiment.” We’ve only got one shot at this. Let’s be careful.

CURWOOD: In 2017 I sat down with E.O. Wilson at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts to discuss the big idea behind his book “Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life.”

WILSON: What we need to do is try for a moonshot, and the moonshot is to set aside half the surface of the land and half the surface of the sea as a reserve, a reserve that doesn’t exclude people by any means – Indigenous people are, in fact, encouraged to enjoy them and continue their way of life – but, if we could give half of the Earth primarily to the millions of other species that inhabit the Earth with us, then we would be able to save about 80 to 90 percent of the species, bring the extinction level down what it was before the coming of humanity. That would be a successful moonshot.

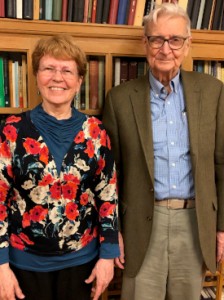

CURWOOD: That bold plan has inspired roughly 70 countries to commit to protecting at least 30% of their land and oceans by 2030 as a first step. Jane Lubchenco is a marine ecologist and Oregon State University Distinguished Professor who is currently serving as Deputy Director for Climate and Environment in the White House. She worked with both E.O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy over five decades and joins me now to help remember their work. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Jane!

CURWOOD: It’s so great to talk with you now, again. Now, each of these men were giants in the field of conservation biology in their own right, and we’ll talk about Tom Lovejoy’s work on forests and climate change in a few minutes. But first, let’s talk about E. O. Wilson. What do you think were his most important contributions?

LUBCHENCO: Oh, my gosh, he made so many, it’s hard to know where to start. Ed was a consummate naturalist. He was just a keen observer of the natural world. Obviously, ants were his passion and his lifelong love, you know, throughout his career. But he was able to build on those observations, and create really innovative breakthroughs in multiple areas. For example, he really pioneered new ideas about how ants communicate with one another. So breakthroughs in ant biology, ant pheromones, was one really big contribution. Another was what is called the Theory of Island Biogeography, which really focuses on, what are the guiding principles behind the number of species that you find on islands or in fragments of habitat?

That was a theory that was both created mathematically, with Robert MacArthur, and then tested experimentally, with one of Ed’s graduate students, Dan Simberloff. And that theory of island biogeography has really formed the foundation of modern conservation biology. It enabled people to think about, where do we want conservation parcels to be, how big should they be? How should they be connected to one another? Etcetera. Ed also, though, was a pioneer in creating new ideas about how people connect to nature, and how nature influences people. And he created this concept of biophilia, which suggests that humans have an innate connection to nature, they’re drawn to nature. All of this was, you know — many, many different contributions that he made. But again, grounded in very detailed, keen observations, but resulting in some grand theories and grand vision.

CURWOOD: Yeah, Ed Wilson was really amazing, and actually helped me in my work, Jane, I mean, obviously, covering the whole question of conservation and ecology. But as he laid out his biophilia hypothesis to me, that we evolved with all these other creatures, and there are things in our genes, or maybe we talk about epigenetics these days, I came to understand media. What do I mean? I came to understand that we evolved for many thousands of years not knowing the images or sounds of other people that we actually hadn’t been with. And that I began to understand why so many people would treat people as almost members of their family that they didn’t know, because they’d seen them on television or heard them on the radio or something. It’s how certain, frankly, politicians got elected from Fred Thompson to Ronald Reagan. It is how if I, I said to you, isn’t it a shame what happened to Tom and Nicole? You might know who I’m talking about, right? And it gave me a better understanding of how it is that we use images and voices in media. And I’m really grateful to Ed for that insight.

LUBCHENCO: You know, Steve, he really had a similar influence on many, many people. He was so adept at being able to explain something, but to do it in a way that would then trigger new thoughts on the part of the person he was interacting with. He was a very gifted teacher for that reason, you know, he would stimulate ideas and encourage others to sort of take them on to the next level and, and make them relevant to their lives.

CURWOOD: So tell me, just share with us a moment that you remember from working with, with Ed Wilson; I know there are many but what comes to mind?

LUBCHENCO: I was a graduate student at Harvard in the ’70s, and then an assistant professor, and it was a time when there was a lot of tension in the Department of Biology, because molecular biology was really on the rise. And many of the leaders of molecular and cellular biology, but Jim Watson in particular, were very arrogant about ecology, evolution, systematics and really dismissed that field as just a bunch of stamp collectors.

And, you know, being dismissed and marginalized to some — and it was to Ed — was very powerful motivation to show that, in fact, the science of ecology, of evolution, were actually legitimate in their own right, and not yesterday’s science but tomorrow’s science. And in the interim, we’ve seen a coming together of those threads in ways that is very exciting and appropriate. But at the time, there was this real tension. And Ed was bearing the brunt of much of this within the department. But being in his lab with his students, seeing these just extensive colonies of ants all over his lab, he would just light up and get so excited talking about his ants.

And he would start talking about new big ideas, and the graduate students, the other folks who were in the room, it was just palpable excitement, that provided a really powerful antidote to a lot of the tension that was in the department more broadly. So just his excitement, his enthusiasm. He was, he was just like a little kid in a candy shop! He was just so over the top excited and it was infectious.

CURWOOD: It was! And, you know, Harvard wasn’t very generous to E. O. Wilson to begin with, they didn’t really want to give him tenure. And they thought that they were sticking him over in the museum with his ants. But you know, all through the years, he kept his office in the museum. And if you went by to see him, he’d show you the leaf cutters, those kinds of ants, he’d get all excited. What a gift. And I, you know, I think he kept the excitement right up to the end. So what do you make of his notion of half-Earth? How does that compare with the notion of, you know, conserving 30% of the biosphere by say, 2030?

LUBCHENCO: Ed was a big thinker, and he didn’t do things halfway. But when he did them, they were solidly grounded in evidence, in good science. And through the years, and his extensive travels, he really became quite concerned about the sixth mass extinction event of biodiversity, the first one in the whole history of Earth that was being caused by people. And he saw firsthand the numbers but also the devastation in many different habitats. And he became very, very concerned about the future of the planet, the future of people, in part because we were losing so many species. And this led him to appreciate the importance of protected areas. And he developed this concept of protecting half of the planet for nature, an idea that many dismissed as completely impossible, because at the time, there was maybe 3% of the ocean that was fully protected, and maybe 17% of the land. So the idea of 50% was just mind boggling, and still is to many.

Nonetheless, he became a staunch champion, very eloquent in his speaking and his writing, focusing on the importance of saving nature, not only for its own sake, but also for our sake. And that concept has gained a lot of support from colleagues and others. The fact that many countries are focused on 30% is quite remarkable, actually. It, you know, remains to be seen how effective that protection is; it really is important what type of protection, you know, something that is fully protected is really, really different from something that’s only lightly or marginally protected. So the devil is in the details with respect to the execution. Nonetheless, his idea was a bold challenge, and an inspiration to many people.

CURWOOD: So E. O. Wilson was a giant, certainly in this field of biological diversity. And oh, by the way, he happened to have a couple of Pulitzer Prizes for his nonfiction writing about ants and things, and he will be talked about for many generations.

>>>>>>………………>>>>>>………………>>>>>>

Listen to the Broadcast Here ~ Living on Earth: Remembering Naturalist E O Wilson