From an Article by Emmie Halter, Cavalier Daily, Univ. of Virginia, November 28, 2021

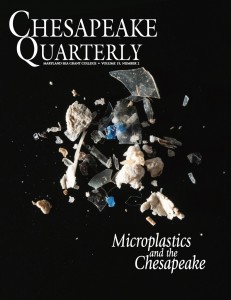

Microplastic waste has become a serious threat to the ecosystem — plastic pollution in particular has grown exponentially in the past decade within Virginia, leading to disruption of the Chesapeake Bay and other large bodies of water. University researchers explain the significant harm that microplastics can have on the environment, particularly in the Chesapeake Bay, and discuss plans of action to combat this detrimental effect.

Microplastics are categorized as plastic particles less than 5 millimeters in size. These often enter the ocean through sewage systems and infiltrate soil and the air we breathe. Initially, researchers only knew of microplastics as the microscopic particles formed by larger plastic waste that was broken down by the sun. However, new findings have confirmed that microplastics come from the synthetic fibers in clothing and microbeads from cosmetic products, such as face exfoliants.

Research on microplastics is minimal, and as a result, researchers do not know the specific effects microplastics have on the environment. For other environmental issues such as landfill waste, pollution and the lack of fossil fuels, researchers have come up with timelines and proposed action plans — this has not yet been developed for microplastics, however.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the U.S. Department of Commerce has voiced concerns about the lack of a large-scale and long-term collective database that contains visual survey information of microplastics along coasts and in the open ocean in order to support microplastic research. As a solution, the NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information created the Marine Microplastic Database this year, a publicly accessible and regularly updated collection of global microplastic data from researchers around the world.

Virginia Governor Ralph Northam signed Executive Order 77 in March, which outlines a plan to phase out single-use plastics and reduce solid waste at state agencies. In response to the order, the University created a single-use plastic reduction policy, which began with eliminating plastic waste in dining halls and replacing single-use plastic with sustainable and reusable takeaway containers and compostable silverware. The University is also looking into expanding their composting facilities and minimizing plastic bag use under this initiative.

Similar initiatives have been implemented throughout the nation, and environmental concerns based on plastic pollution have pushed retailers to provide more sustainable bag options, pilot the trend of reusable containers and make plastic straws a rarity. Environmentally-conscious consumers have even boycotted stores that utilize single-use plastics.

Large plastics make their way into the ocean frequently and are easier to remove from the water compared to microplastics, which must be either filtered out of the ocean or entirely prevented from entering the ocean. The existence of plastics in large bodies of water results in a multitude of issues — notably, the disruption of the ecosystem when animals ingest plastics and release toxic gas and foods containing tiny plastics.

Asst. Engineering Prof. Lindsay Ivey-Burden has conducted research in environmental engineering — specifically engineering for a more sustainable future. Ivey-Burden explained further how these unsustainable materials end up in our environment. “When anything with synthetic fibers and polyester goes in the washer, the fibers sort of come out and they form very small micro [and] nano-plastics,” Ivey-Burden said. “And so then that goes into the wastewater system and back into the environment.”

Another way microplastics enter our oceans is through cosmetic products, especially those labeled as exfoliants. Exfoliants contain microbeads, which produce an abrasion towards the skin that removes dead skin cells from the surface of the face. These microbeads easily pass through household water filter systems and travel to large bodies of water.

In Virginia specifically, this affects the coast and its marine life. One of the most common ways microplastics damage the coastal system is through the oysters in the Chesapeake Bay. “Microplastics in the water make it much harder for [the oysters] to filter the water — which they’re supposed to do because they’re trying to eat all the algae — and they end up eating a bunch of plastic instead of algae,” Ivey-Burden said.

This leads the oysters to be put under an immense amount of stress. In order to fulfill their nutritional needs, they must filter through much more water in order to consume enough algae due to the alarming algae-plastic ratio present in the bay.

Certain areas of the Chesapeake Bay also serve as hot spots for microplastics, acting as breeding grounds for chemicals and diseases that are picked up by microplastics and transported into the bay. Shorelines and underwater grass beds are the most common hot spots because it is easy for microplastics to settle in these areas. The black sea bass — a local fish commonly served at restaurants in coastal Virginia — is just one of the marine animals that feed near these hotspots and ingest the microplastics.

While studies show that most microplastics do not move to the muscle tissue of fish — the part consumed by humans — scientists are still concerned with the effect of microplastics on human health. It is difficult to determine the individual impacts of these plastics on consumers as we are constantly in contact with microplastics, from bottled and tap water to clothing. Additionally, researchers know very little about the levels of toxicity that can hurt humans as well as how food chain processes may affect the toxicity of plastics.

Environmental and material scientists have been researching the toxicity of plastic materials and the solutions needed to decrease this toxicity to people and the environment. Researchers have explored solutions to microplastic waste, but some of these solutions are costly and may cause further destruction to the environment. Water filtration systems, for example, are one of the most discussed solutions. Filtration systems utilizing magnets, tiny nets and vacuums have all been tested by different researchers, but it is nearly impossible to filter out such small pieces of plastic without filtering out very crucial marine organisms as well.

Robert Hale, microplastic expert and head researcher at the Virginia Institute for Marine Science, explained that implementing a filtration system is not realistic. “There are not just microplastics in the ocean, there are other organisms — especially floating organisms — that will get weeded out too,” Hale said. “There is just no way for these filters to sort effectively.”

Other solutions, such as creating more sustainable clothing, eliminating single-use plastics and establishing filtration systems in washing machines are all viable and would have a large impact on microplastic waste. However, from a cost standpoint, the likelihood that the general public will react favorably to increased taxes as a way to fund initiatives that stop plastic waste is very low. “The cost efficiency of plastic ends up feeding the monster and makes it very difficult for big corporations to increase production costs in order to be more environmentally friendly,” Hale said.

In order to eliminate microplastics, scientists agree that toxic additives that are in plastic waste must first be removed. Assoc. Engineering Prof. David Green has been studying plastic waste for much of his career, specifically plastic as a material and the microscopic properties associated with it. “By trying to remove certain additives that have proven to be toxic — things like car plasticizers, stabilizers and pigments — and making this plastic particle, but trying to design it so that when it gets wet and it gets into the landfill, that it doesn’t degrade off,” Green said.

Green also agreed that general reduction of plastics would help to eliminate microplastics. The elimination of single-use plastics at the University is a plan that, if modeled at other universities across the country, could make a big difference.

#######………………#######………………#######

See Also: Chesapeake Quarterly : Volume 19, Number 2 : Rona Kobell, Hazards, Large and Small, Dec. 2020

Scientists are looking closely at these tiny microplastic hazards and trying to assess their harm and reduce their numbers. Neither is an easy task. In this issue, we explore these dangers invisible to most of us. We’ll also talk about how Maryland Sea Grant is working with high school teachers to help them identify microplastics in labs with their students.