Fracking, Freedom and Community in America

From the Book Review by Abraham Gutman, Los Angeles Review of Books, August 1, 2021

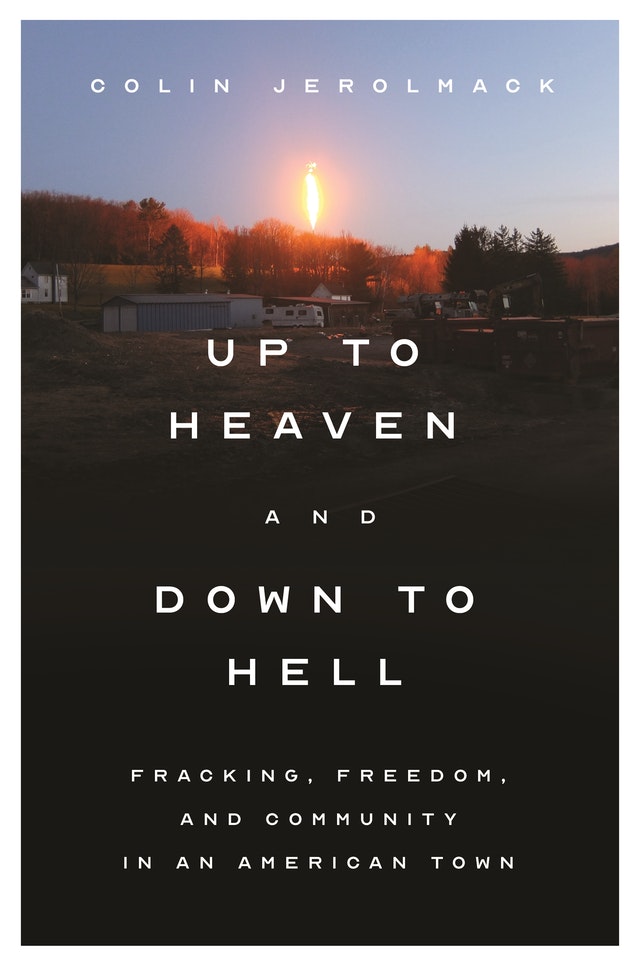

REPRESENTATIVES of Anadarko Petroleum came knocking on George Hagemeyer’s door in rural Northeastern Pennsylvania and offered to lease the mineral rights under his property, but he didn’t see the need to consult anyone else. This was his land: cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos — up to heaven and down to hell. But within a few years, he stood up in a town hall and told people that fracking robbed him from a crucial part of his identity — the nature of his land.

Hagemeyer is one of the protagonists of Up to Heaven and Down to Hell: Fracking, Freedom, and Community in an American Town by New York University climate sociologist Colin Jerolmack. He could have become the poster boy of the anti-fracking movement, but he didn’t — nor did he want to be. In fact, he didn’t view “fractivists” as being on his side at all.

Up to Heaven and Down to Hell is an important story about a moment when urban and rural could have united against fracking, and the government could have proven its worth to disillusioned rural constituents. Instead, corporate lobbying and the nation’s cultural divide led to no change at all.

For eight months in 2013, Jerolmack lived in Williamsport, Pennsylvania — the “big city” next to Hagemeyer, population 29,000. Unlike Eliza Griswold’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America, in which a woman seeks answers for her children’s illnesses after fracking comes to town, Jerolmack focuses on much more benign and pervasive harms. His book is more similar in scope to Seamus McGraw’s The End of Country: Dispatches from the Frack Zone.

Fracking is the process of retrieving natural gas from deep rock formations, called shale, that were once thought to be impermeable. One of these formations is the Marcellus Shale, which sits miles under the western half of Pennsylvania. When the shale boom started in the end of the 2000s, “landmen,” armed with mineral rights leases, flooded in.

It sounded like a good deal. Drake Saxton, a retiree who owned a bed and breakfast on a pastoral quiet escape, described the landman pitch as: “We’re prepared to offer ya all this money, but really, when we’re done, you won’t even know we were there.”

Fracking well pads might be located in pastoral areas, but extracting gas from deep shales requires heavy industry — and a lot of water. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of water, lubricants, chemicals, and sand are injected into the well to fracture the rock, and hundreds of big rig trucks clog the roads. Hagemeyer became a tenant on his own property. He exploded when an Anadarko employee pulled a stop sign in front of his car on the access road to his house. “They’re trespassing,” he complained.

But no one had an incentive to refuse the payouts. Cindy Bower, a self-proclaimed environmentalist with a flaring well pad about 100 yards from her home, told Jerolmack:

The only compensation for everything that’s happening to us is money. If they could have guaranteed me that the noise stops at the property line, any possible contamination stops at the property line, the odor stops at the property line — if they could guarantee me that, that my property would never be affected, I wouldn’t have leased.

Nearly every person Jerolmack talks to is unhappy with the oil and gas industry. And yet, nearly all of them voted for Donald Trump, who overtly supported fracking in his message to Pennsylvania voters in 2020 and inaccurately portrayed Joe Biden as favoring a ban. Trump received 70 percent of the county’s vote.

Why is it that the communities most affected by fracking are the ones opposed to intervention? Because the government was acting in a way that only confirmed anti-government preconceptions. Pennsylvania took away all the power from localities — including explicitly prohibiting municipalities from zoning out fracking. While leasing land was an individual decision, permitting for drilling and pipelines was supposed to be public because of its impact on the commons. Contentious town halls approved projects the community opposed. Residents realized decisions were being made for them in Harrisburg before the meetings ever started.

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection seemed to be in the pockets of oil and gas, more concerned with approving permits than protecting the environment. Locals had good reason for suspicion: Michael Krancer, who was DEP secretary from 2011 to 2013, became a fracking lobbyist.

The environmental fractivists weren’t much better. While local landowners fought to protect their land and rural lifestyles, liberal urban outsiders came to lecture and escalate tensions. Jerolmack describes local fear that a proposed ban was “a Trojan horse that would strip away home rule and property rights, even though fractivists sold it as a way to protect vulnerable rural communities.”

By failing to acknowledge the actual local grievances, which had much more to do with truck traffic than leaked methane’s impact on climate change, fractivists lost the support of the people they claimed to advocate for. They also lost the most effective messengers against fracking: those most harmed.

Unfortunately, Up to Heaven and Down to Hell ends before some real victories against fracking occur. After state courts struck down the preemption on local bans, some communities joined together to prevent industry from coming to their towns. Some of those communities are white and conservative — like Oakmont Borough — and others look very different — like the predominantly Black town of East Pittsburgh.

Jerolmack notes “there was never a collective referendum” on the issue in the form of a “direct citizen vote at the federal or state level, or a congressional roll call vote or hearing.” But there have been many local referendums, and often they went against industry. People have been willing to vote for common good when the vote was on a level of government that they trusted.

The sovereignty of landowners looms large in the fracking debate. Up to Heaven and Down to Hell suggests that there is another competing ideal: government of the people, by the people, and for the people. Had fractivists talked about reclaiming control over Williamsport instead of lecturing about climate change, perhaps people like Hagemeyer would have even led the fight.

>> Abraham Gutman is an opinion staff writer at The Philadelphia Inquirer.

###