Marcellus & Utica shale region struggles for economic progress

Natural gas production boom was a bust for Appalachia, report urges economic transition

From an Article by Mike Tony, Charleston Gazette Mail, July 21, 2021

Appalachia’s natural gas boom turned out to be an economic bust that local and state officials can rebound from if they embrace the rising clean energy economy.

That’s the bottom line of two bottom-line-focused reports released Tuesday by nonprofit think tank Ohio River Valley Institute making an economic case for transitioning away from fossil fuels, especially natural gas development that has failed to convert production into prosperity.

“We know that the Appalachian natural gas boom hasn’t just failed to deliver growth and jobs and prosperity so far. We now know that it’s structurally incapable of doing so,” Ohio River Valley Institute senior researcher Sean O’Leary contended during a webinar on the reports Tuesday. “[That] means that a lot of economic development strategies in the region need to be rethought.”

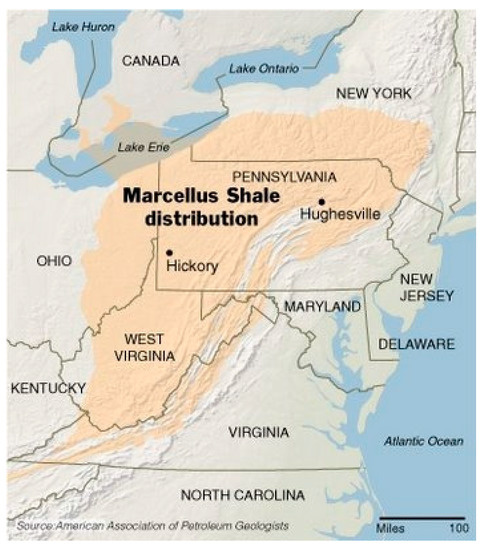

The Ohio River Valley Institute’s analysis focuses on changes in income, jobs, population and gross domestic product — the total market value of goods and services produced — in 22 counties in West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania from 2008 to 2019 that suggest a rise natural gas production in that span did little to lift up the economies in those counties.

One of the reports calls those 22 counties — which include Doddridge, Harrison, Marshall, Ohio, Ritchie, Tyler and Wetzel counties in West Virginia — “Frackalachia” based on the slang term for hydraulic fracturing of deep rock formations to extract natural gas or oil.

Jobs increased in the counties that comprise “Frackalachia” by just 1.6% from 2008 to 2019, 2.3 percentage points behind all West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania counties and 8.3 percentage points below the national average, the report notes.

The report concludes that a dramatic increase in gross domestic product in “Frackalachia” over the same span that came with the natural gas boom didn’t yield economic prosperity because the boom depended heavily on out-of-state workers and service suppliers, yielded less leasing and royalty income for property owners than expected and generated comparatively little income going to employee compensation.

The report find that from 2008 to 2019, when 97% of gross domestic product growth nationally was realized as personal income, that figure was just 21% in the 22 counties across West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania — something that the study attributes to three quarters of growth in those counties taking place in the mining, quarrying, oil and natural gas extraction sector.

“We’re not looking at this from a pro-fracking or anti-fracking perspective or a pro-industry or anti-industry perspective,” O’Leary said. “We’re looking at the fact that the counties are getting a bad deal economically. Whether you’re pro-industry or anti-industry, pro-fracking or anti-fracking, … you look at the numbers, it’s a bad deal.”

The report highlights a recent study from researchers at the University of Akron and Ball State University finding that micropolitan-area counties with higher quality of life experience higher population and employment growth. The study found no “statistically significant relationship between quality of the business environment and growth in micropolitan areas.”

“This finding should come as no surprise to policymakers in many micropolitan and rural regions and states that have premised economic development strategies on providing the best possible business environment — low taxes and minimal regulation — for the natural gas industry only to be disappointed with the result,” states the report authored by O’Leary, fellow Ohio River Valley Institute staff member Ben Hunkler and three University of Washington researchers.

“We have things like the natural resource curse,” said Amanda Weinstein, an associate economics professor at the University of Akron who co-authored the micropolitan-area county study cited in the Ohio River Valley Institute report. “These areas that tend to extract their natural resources tend to do worse … What we’ve seen in the Appalachian area is that they haven’t invested in that quality of life, making sure that as they take out those resources that they’re doing something to maintain their environment and the physical capital, this kind of natural capital that they have in that area.”

In August 2019, Gov. Jim Justice established a task force to bring manufacturing opportunities to West Virginia ahead of an anticipated expansion of the petrochemical industry in Appalachia. Justice’s office said that expansion would bring billions of dollars in investments and more than 100,000 new jobs to the region.

O’Leary said that will never happen because the natural gas industry doesn’t support a large enough workforce to produce its output, arguing that Appalachia should instead embrace the more labor-intensive energy efficiency industry.

“Energy efficiency is heating, ventilation and air conditioning and insulating, and door and window replacement, things that are done by local suppliers even in relatively small towns,” O’Leary said. “These are very labor-intensive businesses. They’re locally delivered. These are businesses that are done by local contractors, and so when you spend money with them, the money stays in the local economy. They hire local workers, and it has a multiplier effect locally.”

O’Leary noted that residential energy efficiency measures for low and moderate-income residents, along with clean energy technologies and worker retraining, were priorities for economic transition funding in Centralia, Washington, where a plant owner-funded $55 million economic transition plan was finalized in 2011 to help that community deal with the closures of a coal mine and plant.

The Ohio River Valley Institute’s other report released Tuesday highlights that transition model, which O’Leary has touted as an example replicable in areas like Marshall County, which faces the possible early closure of the American Electric Power-controlled, Mitchell coal-fired generation facility that serves as an economic engine for the county.

Federal infrastructure proposals inching their way through Congress and savings that American Electric Power would realize from closing the facility in 2028 instead of at the end of its planned life in 2040 could fund such a transition plan for Marshall and surrounding counties.

“[T]he concept of economic transition really needs to take root in the region,” O’Leary said.